It seems another reading week and finals period are already upon us and so you know what that means . . . lots of time for watching movies! I mean studying. I mean watching movies while studying . . . wait, that doesn’t work at all. How about watching a movie after a long, full day of studying? Seeing as school is still in session you might as well watch a legally themed movie, right? To reinforce what you are learning in all your classes . . . or to analyze where the screenwriters got things wrong.

It seems another reading week and finals period are already upon us and so you know what that means . . . lots of time for watching movies! I mean studying. I mean watching movies while studying . . . wait, that doesn’t work at all. How about watching a movie after a long, full day of studying? Seeing as school is still in session you might as well watch a legally themed movie, right? To reinforce what you are learning in all your classes . . . or to analyze where the screenwriters got things wrong.

While this week’s blog post is intended to end the semester with a bit of fun, many in the law profession do believe that movies are an excellent learning tool. Kelly Lynn Anders, a lawyer focusing on social media ethics and a former film critic, wrote the book Advocacy to Zealousness: Learning Lawyering Skills from Classic Films. In her book she explores important lawyering skills and how certain films can teach these skills . . . but at this time of year no one needs another book to read!

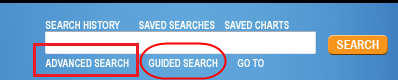

So the question then becomes: how do you find the perfect movie to watch after a full day of outlining? Many of us have Netflix these days (or a friend with a Netflix account) and can watch movies instantly. But as you may have already discovered, searching for movies on Netflix can be a really good way to decide not to watch a movie. You spend a lot of time and effort trying to find something good to watch, scrolling through descriptions, and by the time you finally find one that looks good you’re ready to fall asleep. To top it off, you don’t know if what you choose will be very good because their star system is skewed by 13-year-olds in Oklahoma.

Another problem with Netfix is that it mixes TV shows with movies and no one can afford to get addicted to Law & Order: SVU at this time of year. Sorry Netflix — as a method to search for law-related movies you get a thumb down.

Another problem with Netfix is that it mixes TV shows with movies and no one can afford to get addicted to Law & Order: SVU at this time of year. Sorry Netflix — as a method to search for law-related movies you get a thumb down.

What you really need is a list of the best law movies that you can check out before you go to Netflix. To save you the time you’d have to spend searching for a good legal movie, I’ve done some of the legwork for you. After searching through some legal movie lists and databases, I found that there aren’t very many, and those that do exist are not always very user friendly. For instance, while I found a lot of great movies on a list written by a law professor at Louisiana State University Law School, the choice to use black writing on a gray background in 10 point font is not the best way of getting people to frequent your website. Take a look below.

For eye strain formatting reasons this website gets a thumb down.

For eye strain formatting reasons this website gets a thumb down.

Another website, created by a criminal law consultant, provides a pretty good list of criminal law movies and gives you the option of purchasing the movie from Amazon, a very convenient . . . and possibly very costly . . . feature. Still, you may be frustrated by the lack of movie descriptions on the list. It’s hard to pick a movie by only the title, especially when you’re not a fan of horror movies and have been tricked by nondescript titles before.

For lack of any movie descriptions, this website gets a thumb down.

For lack of any movie descriptions, this website gets a thumb down.

The ABA Journal has a list of the top 25 legal movies ever made (according to their membership). But you may find this list tiresome because you have to scroll through all twenty-five movies to view each one. The ABA Journal gets points for style, but not for efficiency. Still, I am going to give this list one thumb up because it mentions some great movies and includes nice thumbnail descriptions of all of them — like The Paper Chase below — a law school movie classic.

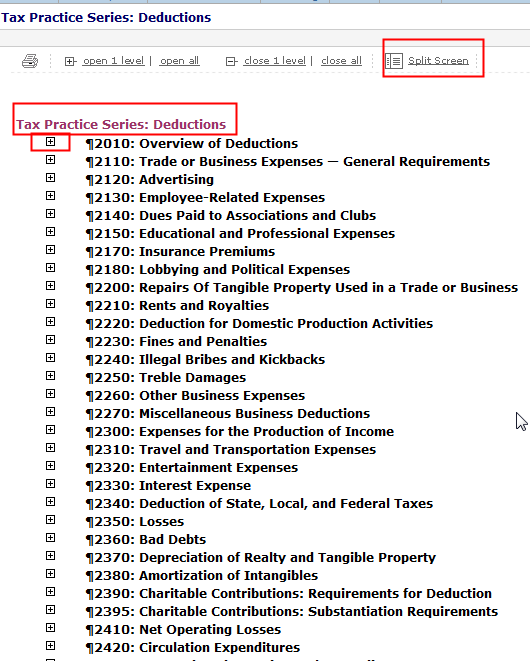

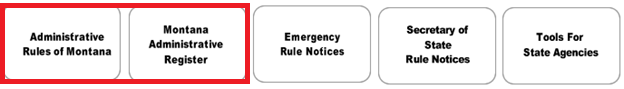

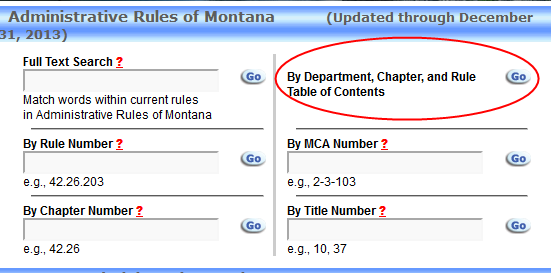

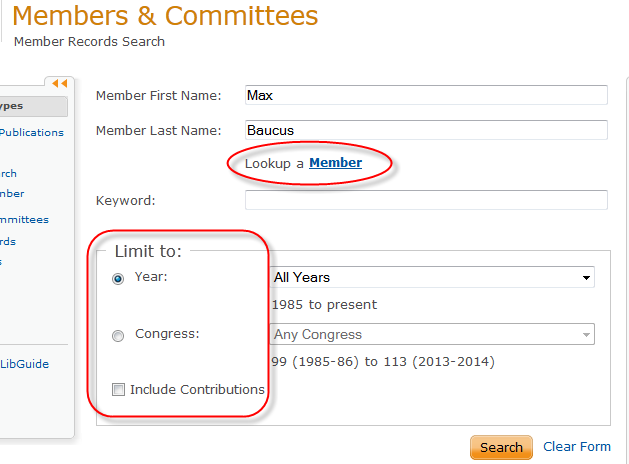

After a lot of searching, one legal movie list stood out above the rest. Not so much because it is very fancy or stylish, but because it is organized in a very user-friendly manner. Ted Tjaden, a lawyer and librarian in Toronto, Canada, created this list. The website gives you helpful search options. You can start simply by viewing an A to Z list of some of the best law related movies out there.

Another search option is by Substantive Law Subject, which offers fifteen legal topics to browse.

Another search option is by Substantive Law Subject, which offers fifteen legal topics to browse.

Anyone need to find a movie to watch for Professor Ford’s family law class? Perhaps Kramer v. Kramer? Open the family law section to find this movie along with a few other excellent family law related movies. Notice below that you get a short description of the movie and can even follow a link to a review if you want more information.

Anyone need to find a movie to watch for Professor Ford’s family law class? Perhaps Kramer v. Kramer? Open the family law section to find this movie along with a few other excellent family law related movies. Notice below that you get a short description of the movie and can even follow a link to a review if you want more information.

Another thing you’ll love about this website is that you can jump straight to comedies or to inspirational movies or to dramas, all of which in some way relate to the law. You can pick a movie based on what mood you’re in and don’t have to be surprised by a tearjerker when what you really need is an evening of legal laughs.

Another thing you’ll love about this website is that you can jump straight to comedies or to inspirational movies or to dramas, all of which in some way relate to the law. You can pick a movie based on what mood you’re in and don’t have to be surprised by a tearjerker when what you really need is an evening of legal laughs.

After finding this site, I couldn’t resist asking our own resident legal writing expert, Professor Howell, for a movie suggestion. Some of you may have figured out that our 1L memo and brief problems are usually filled with characters from current legal movies. In 2012, the characters were pulled out of the movie The Lincoln Lawyer and in 2014, the names came from American Hustle. Points for anyone who knows what the problem was based on last year, because neither Professor Howell nor any current 2Ls I approached can remember! Professor Howell’s pick? He suggests we all take the time to watch The Verdict with the great actor Paul Newman portraying an alcoholic attorney facing a “David v. Goliath” legal battle.

Legal movies can be a great way for all of us to unwind from a day of studying for finals. And who knows, it’s possible that we might even learn a thing or two at the same time. You might need to use these legal movie resources in conjunction with Netflix or Crazy Mike’s, but hopefully one of them might help you procrastinate. Er, I mean study!